How Far Can the Influence of Created Art Forms Reach?

A DEEPER LOOK: PURSUED: TEN KNIGHTS ON THE BARROOM FLOOR (from the notes of Mel R. Jones)

In Jones’s novel, not only does the Christus Consolar statue in the Billings Hall at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, play an important part as one of the novel’s settings, but the sundial placed in the circular terrace in front of the main entrance to this Administrative Building does as well.

One look at this ornamental bronze sundial captivates one’s curiosity with its unusual design. It’s not a traditional sundial with a flat dial and an upright triangular blade to cast shadows.

Instead it features a partial cylinder held upright at the proper angle supported by four pillars. A bead on a wire strewn between the four pillars casts a shadow on the cylindrical plate, annotating the hour. More unusual, there are only five such identical sundials in existence, the fifth’s location yet to be found by sundial enthusiasts. The North American Sundial Society (NASS) believes it went missing years ago near Portland, Maine.

This new and improved version of the sundial was patented by scientist and inventor Albert Cushing Crehore of Yonkers, New York, in 1905 and was donated to Johns Hopkins Hospital by trustee George McGaw in the same year. Its weathered inscription reads, “One hour alone is in thy hands, the hour on which the shadow stands.”

As the novel opens in 1973, the protagonist, forensic pathologist, Dr. Emerson Stanek, couldn’t care less about this iconic sundial and its message. He and the Johns Hopkins dons and his mentor, Dr. Thomas Haviland, who are on his committee to decide whether his cancer research project qualifies for a grant, approach the sundial on their way to a conference area. They stop at the sundial where Dr. Haviland asks his colleagues what meaning each attributes to the saying on the sundial. Haviland reminds Stanek of the pathology department tradition that each time the group passes the sundial, they devise new meanings for its message.

One doctor’s contribution reminds them “one’s courage is greatest at the beginning of a journey.” Haviland’s contribution is the first principle of pathology used in his lectures. He asks Stanek if he remembers, and Stanek replies, “’Look intently enough at anything, and you’ll see something that might otherwise escape you.’” When Haviland asks Stanek to make his own offering, the pathologist’s mind, filled with repressed memories of past suffering in this area, tersely replies, “Never paid much attention to monuments strewn along the path of scientific progress on this campus.”

But Stanek can’t escape the committee’s attention, even after his outburst about estranged family relationships when reminded by Haviland the Stanek Foundation maintains the old sundial and other monuments. He finally relents and offers a clipped message designed to stop the committee from frittering away time on campus monuments when his cancer research project is awaiting its attention. He says, “All hours offer opportunities, but wasted ones kill all potential in the end.”

Despite his efforts to dismiss the sundial and its message, Stanek comes across it once again. As a favor to his mentor, he takes notes for him on a bundle of papers about a crime scene within a crashed WW II B-24 Liberator bomber from 1943 recently discovered in the Southern Highlands District of Papua New Guinea. The sundial’s image and message come into his view as he examines a piece of physical evidence offered to Haviland to interest him in taking on the B-24 case investigation.

Stanek picks up a Zippo lighter originally found clutched in a severed hand discovered inside the WW II B-24 bomber wreckage. The lighter has the saying, “One hour alone is in thy hands, the hour on which the shadow stands” along with an image of the sundial inscribed on it.

At first Stanek discounts the connection between the Johns Hopkins sundial and its message and the one on the Zippo lighter. Baltimore and New Guinea, so distant from one another in every way, seem to Stanek as too incredible a connection to be linked as a substantial clue in the crime scene investigation.

As Stanek inadvertently becomes involved in the inquiry in New Guinea, we wonder if his “hours” will be “wasted” there, or whether his “courage at the beginning of his journey” will last through the challenges inherent in the situation, or if he will “look at anything intently enough to see something that might otherwise escape him” in the mysterious and deadly intrigue the crime investigation reveals? Or will he discover a hidden connection that ties the sundial’s message in Baltimore to the same one on the Zippo lighter?

What’s more, will Stanek discover the human connectedness beyond science he has shut out of his life since the betrayal and injustice suffered in his youth? Will Stanek “look beyond science to probe the human soul when survival depends upon the pursued become the pursuers”?

Stanek’s choice is our choice as well. Does the sun shine on your “sundial,” or is it a cloudy day in your life? What meaning will you, and all of us, choose to see in the sundial’s message whatever the circumstances? “One hour alone is in thy hands, the hour on which the shadow stands.”

[avatar]Marian[/avatar]

The fictional protagonist, forensic pathologist Dr. Emerson Stanek, experiences the worst emotional injustice of his life (which paradoxically also holds the possibility of the best) at the feet of the ten foot Carrara marble statue of the Christus Consolator in the rotunda of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

The fictional protagonist, forensic pathologist Dr. Emerson Stanek, experiences the worst emotional injustice of his life (which paradoxically also holds the possibility of the best) at the feet of the ten foot Carrara marble statue of the Christus Consolator in the rotunda of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. Having served two tours of duty in Vietnam, Mel R. Jones wrote in the acknowledgements to his novel, “Those of us who have been involved in the military in one way or another have been sent to protect our country by engaging in war to attain peace—a paradox of human experience that repeats itself generation after generation, century after century.”

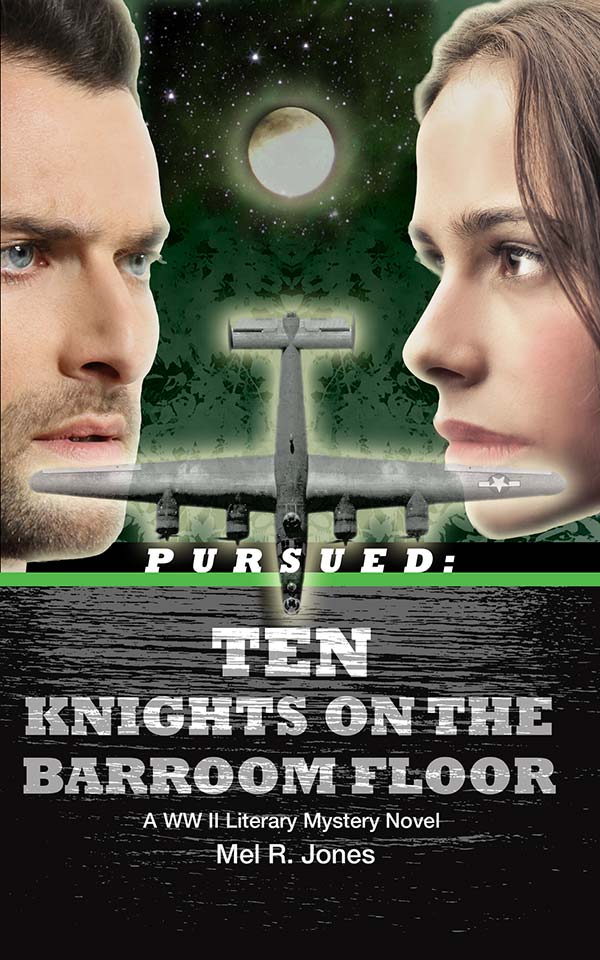

Having served two tours of duty in Vietnam, Mel R. Jones wrote in the acknowledgements to his novel, “Those of us who have been involved in the military in one way or another have been sent to protect our country by engaging in war to attain peace—a paradox of human experience that repeats itself generation after generation, century after century.” You might ask, “What’s with this unusual, paradoxical title, Pursued: Ten Knights on the Barroom Floor? Thoughts might occur to you, such as, “We expect ‘knights’ to be noble defenders in service to the greater good. What are they doing on the ‘barroom floor?’ And ten of them at that! They certainly must be lost to their mission. Does anyone really care if they have fallen? Why try to find, or ‘pursue,’ them?”

You might ask, “What’s with this unusual, paradoxical title, Pursued: Ten Knights on the Barroom Floor? Thoughts might occur to you, such as, “We expect ‘knights’ to be noble defenders in service to the greater good. What are they doing on the ‘barroom floor?’ And ten of them at that! They certainly must be lost to their mission. Does anyone really care if they have fallen? Why try to find, or ‘pursue,’ them?”